The buzz in New York real estate these days is about the new.

WeWork, with its shared office space and youthful aesthetic, has emerged from nowhere to become the city’s biggest tenant. The new World Trade Center is redefining downtown. And on the far west side of Manhattan, the $ 28bn Hudson Yards development has lured the likes of KKR and BlackRock with gleaming, new office towers that promise ultra-efficiency and a wealth of amenities.

So why has Aby Rosen, the German-born tycoon who made his fortune buying at the bottom of New York’s 1990s real estate bust, acquired one of the city’s oldest skyscrapers, the art deco Chrysler building?

“It has lost a little bit of its relevance. But it has not lost its beauty or importance,” said Mr Rosen, calling the building “an American icon”.

In his quest to make Chrysler pay off, Mr Rosen may have his work cut out. The sprawling ceiling mural in the pink marble lobby still has the power to make tourists tilt their gazes skyward in awe. But on the arcade floor below, many of the storefronts are shuttered. On a recent afternoon, in one of the few that was open — a dry cleaners — an old woman was leaning over a sewing machine under pale fluorescent light.

Chrysler’s previous owner, the Abu Dhabi Investment Fund, gave up on the storied building. Having paid $ 800m for a 90 per cent stake in it in 2008, it agreed to sell the building to Mr Rosen’s RFR Holdings at a deep discount: just $ 151m.

The Emiratis were motivated to unload the building because it is saddled with a ground lease — annual rent that must be paid to the owner of the underlying land — that shot up from $ 7m to $ 32.5m last year, with further increases to come. After years of neglect, the building is also in need of tens of millions of dollars in refurbishments.

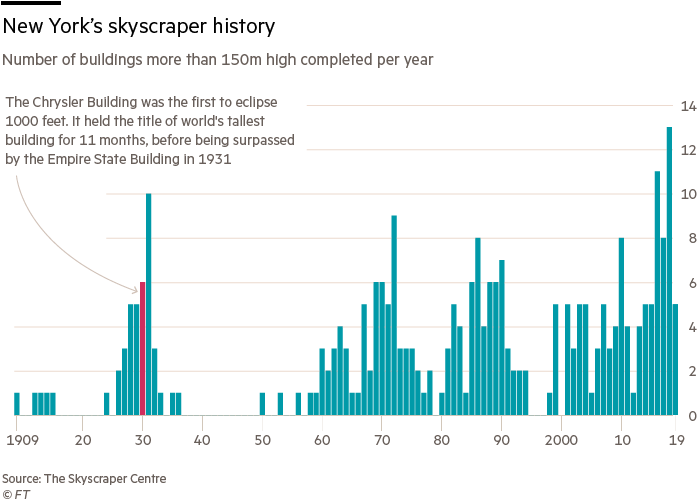

“Daunting” is how one rival described Chrysler, which was the world’s tallest building when it went up in 1930 until the Empire State Building topped it the next year.

Mr Rosen is contending with other challenges at the moment. The ground rent at his prized Lever House headquarters on Park Avenue is also due to spike in 2023, raising speculation that RFR may be forced out of the famed glass box.

But when the tycoon, known for a staggering art collection that includes works by Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Damien Hirst, speaks about Chrysler he sounds more like an impassioned collector than a calculating developer.

“It was for sale a long time ago and we were not ready and we missed it,” he said. “Sometimes you get a second chance and you grab it.”

Throughout his career, he has displayed a nous for buying New York landmarks and shining them like pennies — even if it means paying over the odds to do so. His mission, as he describes it, is to rediscover a unique building’s soul. If he succeeds, then the rents usually take care of themselves.

“In my mind, you are a custodian of those landmarks for a period of time until you pass them on to the next person. They don’t trade as often as other buildings because they are love affairs and they take a while to put your imprint on them,” he explained.

Hudson Yards, he acknowledged, was a “phenomenal project”. But he also cast a few well-aimed stones at its glass façade. Chief among them was that its far-west location — once a derelict part of town — lacked the buzz of Manhattan’s traditional centres of culture and commerce. Chrysler stands on the east side of Midtown, opposite Grand Central Station.

“They put the Shed [arts centre] there, which is nice, but it doesn’t really replace the classic New York environments of side-street shopping and cafés and restaurants and, you know, churches and synagogues and, who knows what? It took hundreds of years to develop this here,” Mr Rosen said.

He also found something distasteful about Hudson Yards’ relentless gloss. “It’s going to be super high-end office, super high-end residential, and with super high-end retail. It’s going to be . . . 10 square blocks for the rich. And that’s not interesting, as you know,” he said. “We’re becoming a city of the rich, and that’s boring.”

RFR is not opposed to the rich. It has been trying to interest foreign buyers in a luxury Manhattan condominium tower — a sleek Norman Foster-designed high-rise on 53rd Street — built in partnership with Vanke, the Chinese developer. The market is soft and sales are slow.

Mr Rosen developed a sensibility for historic buildings growing up in Europe. His parents were Holocaust survivors who settled after the war in, of all places, Germany. They could not make it to the US and were wary of the violence in a fledgling Israel. “Maybe they felt special or maybe they felt safe and protected because nobody would do those things again,” Mr Rosen speculated.

After studying law, Mr Rosen eventually made his way to New York in the late 1980s, where he gravitated to the art scene. He and a childhood friend, Michael Fuchs, made their mark in real estate using German capital to buy up buildings in the ashes of recession and then enlist top architects to refresh them.

“I’m into modern and classics. I like things that will look good 20 years from now,” he said, explaining his taste. “I’m not the guy who builds the curvy building that hangs over and does some weird stuff — that’s not me.”

Many developers shun properties like the Chrysler building because of the hassle of dealing with New York’s landmarks preservation commission. In a business where time is of the essence — delays mean lost rent — years spent haggling with preservationists about whether elevator doors can be replaced or a window upgraded is a costly proposition.

In spite of some well-publicised scrapes with preservationists, the restless Mr Rosen — who calls his trade “masochistic” — said he appreciates the discipline they have imposed on him. He also views landmarks as good business.

“Building a brand new building today costs you a thousand bucks a foot anyhow. So you might as well buy something for $ 800 existing, or $ 700 existing, and restore it for another $ 200 or $ 300 per foot, and you have a historic building,” he explained. “If you look at the tech companies, you look at the VC capital and all those youngsters who are going to be running the next America, they all seek kind of cool buildings that have some sort of history.”

That is not to say he always knows what to do with an old building. He paid $ 26m for a former animal hospital on Bond Street in Manhattan’s NoHo neighbourhood in 2015. The 1913 building had become a women’s shelter but still featured a complicated set of internal ramps to convey horses to upper floors. (The roof was once used for autopsies). The windows were at an awkward horse height.

“When you saw this, it was scary,” said Sheldon Werdiger, an architect and RFR executive who has the challenge of helping Mr Rosen realise his visions. After some wrangling with the landmarks commission, it was gutted and is now a honeycomb of digital pop-up stores.

Mr Rosen has bought two other buildings in the area, including a former bank that is now a graffiti-strewn skateboard shop and photo agency. “That area is one of my favourite parts of New York City,” he said of a once-gritty precinct that has tipped into trendy. “Great architecture, great cast-iron buildings, great cobblestones. And that’s where the action is right now.”

His best-known projects are uptown, including his cherished Seagram Building, the mid-century masterpiece on Park Avenue designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. RFR acquired it in 2000. Mr Rosen keeps watch over its bronze-and-glass façade from his office across the street at Lever House. The exacting owner has been known over the years to chastise Seagram tenants for installing the wrong hued lightbulbs.

A few years ago he outraged a certain New York set when he pushed out the Four Seasons restaurant, Manhattan’s ultimate power lunch destination, from Seagram to bring in new blood. Mr Rosen had previewed his disdain months earlier by removing an enormous Picasso tapestry, “Le Tricorne”, that was for more than 50 years the Four Seasons’ centrepiece. Preservationists were aghast and fought the move for months. The tapestry now hangs at the New-York Historical Society.

Mr Rosen is unapologetic. Preservation, he argues, is not about replacing a building’s every feature, like for like, but reinterpreting it for a new era. Otherwise, he argued, a place like the Four Seasons risked becoming a museum — or a mausoleum.

“It cannot only be slick leather and dark and black and brown where you had cigar-smoking executives sitting,” Mr Rosen said. “Those days are gone. Otherwise you have an empty restaurant. These are dynamic spaces that need to be refreshed and reprogrammed all the time.”

If catering to a younger crowd is more “democratic”, according to Mr Rosen, it may also be more lucrative. “Today, the young people have so much money. They have more money than the old guys, and they like to show it and spend it. So you got to — if you’re a landmark or a restaurant like this — you have to make it au jour.”

Just how Mr Rosen plans to accomplish that at the Chrysler building remains unknown. There is talk of reinterpreting Chrysler’s Americana for a new era, perhaps with some sort of hip diner. RFR is also expected to revive the Cloud Club, a private lunch venue with commanding views from the 67th floor that was once the domain of Walter Chrysler and fellow moguls EF Hutton and Pan American Airways founder Juan Trippe, among others.

“It will take a while to bring back what I think is relevant to the Chrysler building but I think we have an interesting plan,” Mr Rosen said. “In the end, let’s be honest: it’s a lobby, and it’s an elevator and then you have office space. But you’ve got to make it more than just that.”